Hampstead Garden Suburb was the outcome of two things:

• The Garden City movement (inspired by Ebenezer Howard, 1898)

• Henrietta Barnett’s vision of an ideal suburb of large and small dwellings in semi-rural harmony.

It was the 1899 plan to extend the London Underground train to Golders Green that spurred Henrietta Barnett into action. Her country house had views over the surrounding farmland and the prospect of the land being covered with standard poor quality housing, coupled with her personal experience of the poverty and awful living conditions of central London, made her determined that the development should combine town and country in the Garden City ideal.

Both the Suburb and the train line were opened in 1907. The story of the Suburb, below, is adapted from a lecture a century later by Dr Ann Saunders, formerly chair of the Hampstead Garden Suburb Archives Trust. It is a very personal lecture and notes the passing of old values, but the Suburb remains a community where residents join in numerous activities, with local Organisations that continue to thrive.

The bricks and mortar, and the all-important landscaping, are protected by the HGS Trust and by the statutory Conservation Area regulations administered by the London Borough of Barnet. Alterations to buildings therefore require the approval of both bodies. The street scene and public open spaces both fall under Barnet, as part of the Conservation Area, save for the Heath extension which is protected by Act of Parliament and currently maintained by the City of London Corporation.

The Founding of Hampstead Garden Suburb

In 1928, for the coming of age of the Hampstead Garden Suburb, Dame Henrietta Barnett wrote a short account of the inception and foundation of her brainchild. Let us follow the story as she told it.

In 1873, Henrietta Rowland married Samuel Barnett, a poor clergyman, dedicated to the amelioration of the lives of the most unfortunate, caring not only for their souls but also for their minds and bodies. In this work, Henrietta joined him; they drew around them a team of high-minded young men (and some women) which led to the foundation of Toynbee Hall in Whitechapel. Henrietta dreamt of establishing a community so planned that all classes of whatever status, from the highest to the least fortunate, might live together in harmony and mutual support, regardless of financial position, of level of intellect and education, or of physical ability. There must be room for the crippled and blind, as well as for those of impaired intelligence, and all were to be treated equally if not exactly alike. To others, even her husband, her dreams seemed unlikely, simply Utopian.

In 1873, Henrietta Rowland married Samuel Barnett, a poor clergyman, dedicated to the amelioration of the lives of the most unfortunate, caring not only for their souls but also for their minds and bodies. In this work, Henrietta joined him; they drew around them a team of high-minded young men (and some women) which led to the foundation of Toynbee Hall in Whitechapel. Henrietta dreamt of establishing a community so planned that all classes of whatever status, from the highest to the least fortunate, might live together in harmony and mutual support, regardless of financial position, of level of intellect and education, or of physical ability. There must be room for the crippled and blind, as well as for those of impaired intelligence, and all were to be treated equally if not exactly alike. To others, even her husband, her dreams seemed unlikely, simply Utopian.

But her opportunity was to come. After some years of work in Whitechapel, the Barnetts found it imperative for their health to purchase a house overlooking Hampstead Heath to which to retreat for two nights each week. In 1896, while on a voyage to Russia, they met an American entrepreneur, Charles Tyson Yerkes, and he told them of his plans to extend the underground railway system out northwards and that there would be a station by Wyldes Farm. Henrietta immediately imagined rows and rows of little suburban houses, perhaps almost as pinched and cramped as those of Whitechapel, spreading up the slopes to the Heath, and incidentally ruining the prospect from her house on the heights near the Spaniards Inn. She wrote: ‘It therefore became imperative to enlarge the Heath’, so with two important

But her opportunity was to come. After some years of work in Whitechapel, the Barnetts found it imperative for their health to purchase a house overlooking Hampstead Heath to which to retreat for two nights each week. In 1896, while on a voyage to Russia, they met an American entrepreneur, Charles Tyson Yerkes, and he told them of his plans to extend the underground railway system out northwards and that there would be a station by Wyldes Farm. Henrietta immediately imagined rows and rows of little suburban houses, perhaps almost as pinched and cramped as those of Whitechapel, spreading up the slopes to the Heath, and incidentally ruining the prospect from her house on the heights near the Spaniards Inn. She wrote: ‘It therefore became imperative to enlarge the Heath’, so with two important  and philanthropic gentlemen, Lord Eversley and Robert Hunter, and aided by the labours of her devoted companion and secretary, Miss Marion Paterson, thirteen hundred individually targeted letters of appeal were written and addressed, deputations were organised to local authorities, money was raised and eighty acres of land were purchased from Eton College for £43,241 16s. 4d. These formed the Heath Extension and created a buffer zone between London and the isolated crossroad at Golders Green which was to be the destination of this first extension of what has now become the Edgware branch of the Northern Line.

and philanthropic gentlemen, Lord Eversley and Robert Hunter, and aided by the labours of her devoted companion and secretary, Miss Marion Paterson, thirteen hundred individually targeted letters of appeal were written and addressed, deputations were organised to local authorities, money was raised and eighty acres of land were purchased from Eton College for £43,241 16s. 4d. These formed the Heath Extension and created a buffer zone between London and the isolated crossroad at Golders Green which was to be the destination of this first extension of what has now become the Edgware branch of the Northern Line.

This initial campaign lasted five years and, during its course, Henrietta realised that, if only she could persuade Eton College to sell her the rest of the land - some 243 acres - which Henry VIII had bestowed upon the College when he relieved it of what was to become St James’s Park, she could develop there her ideal community. Accordingly, she called upon Mr Sanday, a tall, grave gentleman who administered the estates belonging to the College; the two pored over maps and discussed costs, and he then said:

“Well, Mrs Barnett, I know you, and I believe in you, but you are only a woman, and I doubt if the Eton College Trustees would grant the option of so large and valuable an estate to a woman! Now, if you get a few men behind you it would be all right.”

And that is exactly what Henrietta did.

Before we begin to recount her actions, let us think for a moment about what models she may have had in her mind. The concept of an ideal estate was not a new one. John Nash had realised a picturesque ideal with his arrangement of eccentric circles in Regent’s Park; he was aiming at a countryside, brought into the town - rus in urbe. The textile manufacturer, Titus Salt, had re-sited his mill outside Bradford and during the 1850s had built twenty-two streets containing 850 houses for his employees and their families. George Cadbury, Quaker producer of chocolate in Birmingham, developed Bournville a decade later and, in late 1887, William Lever removed both equipment and work staff from Liverpool to Port Sunlight where the manufacture of soap continued and houses were provided for the workforce. The following year, Ebenezer Howard wrote a small book, The Peaceful Road to Real Reform and four years later he reissued it, enlarged and with a different title, Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1902). That was one of the most influential books of the twentieth century and its effects were felt all over Europe, particularly in France, Germany and Russia, and in the United States of America.

His ideas, which were current before the publications, were eagerly absorbed by two young Yorkshire cousins, Barry Parker and  Raymond Unwin. They became even more closely related when Unwin married Parker’s sister, Ethel. The pair worked on New Earswick outside York, a village founded in 1902 by Joseph Rowntree, another Quaker chocolate manufacturer who followed George Cadbury’s example in providing housing for his staff and their families. Then, in 1904, they were awarded the contract to design Letchworth in Hertfordshire, the first Garden City built on Ebenezer Howard’s principles of the essential importance of light, space and air in the provision of housing. The Unwins moved to Letchworth; both men planned street layouts and designed houses.

Raymond Unwin. They became even more closely related when Unwin married Parker’s sister, Ethel. The pair worked on New Earswick outside York, a village founded in 1902 by Joseph Rowntree, another Quaker chocolate manufacturer who followed George Cadbury’s example in providing housing for his staff and their families. Then, in 1904, they were awarded the contract to design Letchworth in Hertfordshire, the first Garden City built on Ebenezer Howard’s principles of the essential importance of light, space and air in the provision of housing. The Unwins moved to Letchworth; both men planned street layouts and designed houses.

There were other examples of good and interesting planning nearer to London. Richard Shaw had begun work on Bedford Park as early as 1875, there was Brentham, a copartnership development which celebrated its centenary in 1901 with the publication of an excellent history by Alison Reid, and, literally almost within walking distance, there was Frank Stratton’s creation of Village Green beside the Dollis Brook below Church End, Finchley. Dame Henrietta must have known of all these, but let her tell the story of what came next in her own words:

“... a plan had to be made, and the ideals so clamorously occupying my mind had to be set out in architectural drawings and business phraseology. Whenever I have a job on hand it is my wont to read any and everything I can get hold of on the subject, and a certain brown bag, whose ever bulging sides were crammed with reports, lived with me. Among them was a pamphlet by Mr. Raymond Unwin. In September, 1904, I was called suddenly away from Whitechapel by the serious illness of one very dear to me, and stuffing a few more dull documents into the bursting bag, I tore off for the train. Amid the anxieties attending the illness, I read on and on, not even noticing who wrote what, until putting down : I said, “That’s the man for my beautiful green golden scheme,” and I set to work to try and meet him. A few weeks later Lord Brassey introduced us, and then Mr. Unwin reminded me that he had been among our social service followers in Oxford, and both my husband and I recalled him with pleasure.”

For a fee of £100, Unwin prepared a plan for the Suburb which was discussed by the Committee on 19 January 1905, and was annotated freely by Henrietta. She then set about the raising of money with which to buy the remaining 243 acres from Eton.

Taking Mr Sanday’s advice, she assembled what she described as a ‘veritable showman’s happy family, two earls, two lawyers, two free churchmen, a bishop and a woman’. The earls were  Lord Crewe leader of the House of Lords and Lord Gray which was to become Governor General of Canada; the lawyers were Sir John Gorst, an MP and a former solicitor general, and Robert Hunter, whom we have already mentioned, one of the founders of the National Trust; the free churchmen were Walter Hazell and Herbert Marnham, local residents and much respected; the bishop was

Lord Crewe leader of the House of Lords and Lord Gray which was to become Governor General of Canada; the lawyers were Sir John Gorst, an MP and a former solicitor general, and Robert Hunter, whom we have already mentioned, one of the founders of the National Trust; the free churchmen were Walter Hazell and Herbert Marnham, local residents and much respected; the bishop was  Arthur Winnington Ingram, Bishop of London. And there was the indomitable Henrietta herself. Canon Barnett feared for her health but she was unstoppable. She tramped over the fields and ‘toiled through stubbly grass and climbed the hedges’ with Lord Crewe until they reached the central hill where she declared:

Arthur Winnington Ingram, Bishop of London. And there was the indomitable Henrietta herself. Canon Barnett feared for her health but she was unstoppable. She tramped over the fields and ‘toiled through stubbly grass and climbed the hedges’ with Lord Crewe until they reached the central hill where she declared:

“This is the highest place and here we will have the houses for worship and for learning.”

There followed years of fund raising, of letter-writing, of badgering authorities at all levels and of letters and reports to newspapers. In February 1905, Henrietta set out her scheme in The Contemporary Review. She wanted the suburb to be a place where all classes, rich and poor alike, would live together in harmony, the higher ground rents paid by the better-off subsidising artificially low charges to their less affluent neighbours. The estate, she said, must be planned as a whole, the houses not in drab regimented rows but each with its own garden and so sited as not to impinge on another’s outlook. Every street was to be planted with flowering trees, and there were to be all the advantages of a community - houses of prayer, a library, schools, a club house and lecture room, shops, baths, wash houses and playgrounds for small children. No one was to be excluded - the old, the lonely, the very young, the crippled, the mentally distressed - there was to be room for them all. Noise was to be kept to a minimum; trees and woods and the rural nature of the land were to be preserved as far as possible.

She had already annotated Unwin’s original plan firmly. Along the western boundary, furthest away from the newly-opened Underground station at Golders Green, she marked: “This is the 70 acres allotted for the homes of the industrial classes @ 10 to the acre.”

To the north she wrote: “Here will be villas for clerks.”

At the centre she indicated: “This is the 5 acres put aside for the church, the chapel, the library and the club.”

Nearby there were to be ‘some of the richer houses’, and at the north-western corner she wrote:“This is the high ridge from whence some of the more distant views are obtained - & on which the rich will build their houses”.

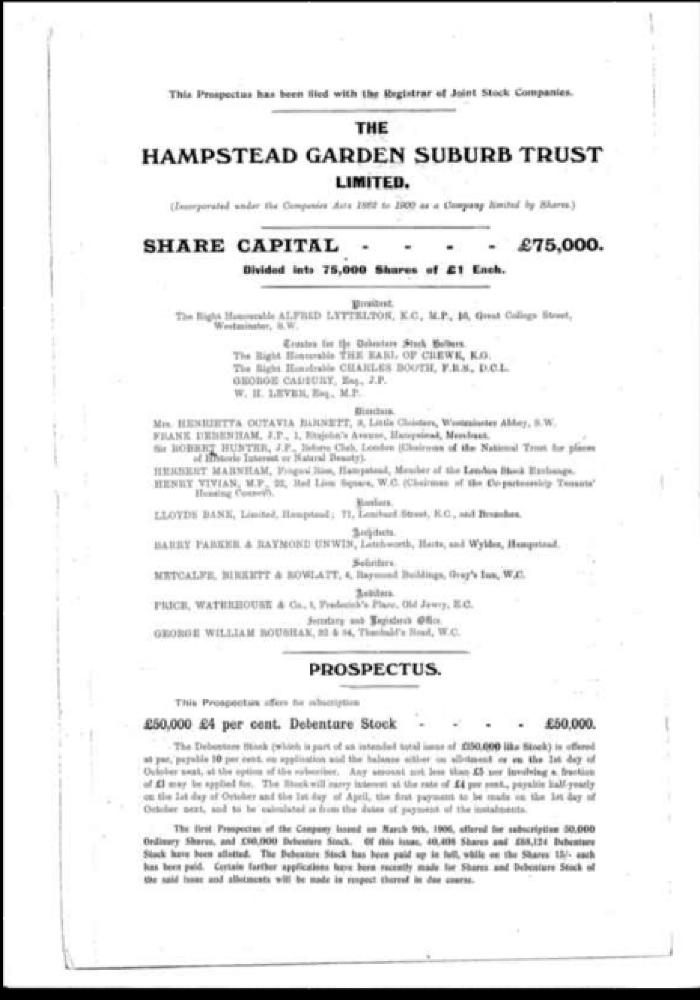

In March 1906, the Committee became a Company; the land was purchased, and Henrietta declared:“... the last time this land changed hands it was under the signature of Henricus Octavus - Henry VIII. - a king who parted with the broad acres to enhance his pleasure. The next time it changed hands the deeds were signed by Henrietta Octavia, not a queen, but a woman, who had for years been a general servant in Whitechapel, and who had bought it on behalf of a public company with the people’s money to provide the people’s homes. That is significant of the recognition of democratic needs and of the change in women’s position.”

The first Company meeting heard triumphantly that seventy-four applications had already been received for building sites, and a further 107 for houses once they were built.  On 2 May, a windy day in 1907, Mrs Barnett turned the first spadeful of soil, a child recited a poem written for the occasion, other children struggled with fluttering ribbons to plait them round a maypole, speeches were delivered and the company adjourned to a marquee in the grounds of the Royal Oak for luncheon. Where the first sod had been cut, a pair of cottages, 140 and 142 Hampstead Way, were soon built; a plaque marks them as the earliest dwellings.

On 2 May, a windy day in 1907, Mrs Barnett turned the first spadeful of soil, a child recited a poem written for the occasion, other children struggled with fluttering ribbons to plait them round a maypole, speeches were delivered and the company adjourned to a marquee in the grounds of the Royal Oak for luncheon. Where the first sod had been cut, a pair of cottages, 140 and 142 Hampstead Way, were soon built; a plaque marks them as the earliest dwellings.

Page 1 of the Prospectus

Full Prospectus

Early photographs show with what speed building progressed in the initial phase of development - nineteen plots were let in a single day on 25 May 1907. By this time, the overall scheme had changed, particularly in the central area, the heart of the suburb, for, although Unwin had been appointed as Architect, yet  E. L. Lutyens, later Sir Edwin, was chosen as Consultant. Lutyens’ fame was already considerable, and was going to become greater when he was chosen to design New Delhi, but his relationship with the Trust, judging from the discreetly worded Minutes, was stormy. His advice was particularly sought for the layout of the Square which was to span the highest ground and to give space to the churches and other public buildings. Unwin had suggested that there should be six structures at this heart of the whole design - a church, a chapel, a public hall, a library with picture gallery and museum, a band-stand, and a Home for young men. There were to be shops and tennis courts around the centre. But by 1907 a much greater formality had been introduced and Central Square was built as it is today - St Jude’s (the same dedication as Canon Barnett’s parish in Whitechapel) to the south, the Free Church to the north and the Institute filling the eastern side. We can only speculate how much more life there would be in the heart of the Suburb had the shops, at least, materialised.

E. L. Lutyens, later Sir Edwin, was chosen as Consultant. Lutyens’ fame was already considerable, and was going to become greater when he was chosen to design New Delhi, but his relationship with the Trust, judging from the discreetly worded Minutes, was stormy. His advice was particularly sought for the layout of the Square which was to span the highest ground and to give space to the churches and other public buildings. Unwin had suggested that there should be six structures at this heart of the whole design - a church, a chapel, a public hall, a library with picture gallery and museum, a band-stand, and a Home for young men. There were to be shops and tennis courts around the centre. But by 1907 a much greater formality had been introduced and Central Square was built as it is today - St Jude’s (the same dedication as Canon Barnett’s parish in Whitechapel) to the south, the Free Church to the north and the Institute filling the eastern side. We can only speculate how much more life there would be in the heart of the Suburb had the shops, at least, materialised.

Nevertheless, development went on fast. Those first two cottages were built between 5 June and 9 October 1908. Two hundred and seventy houses went up in Asmuns Place and Hill and along Hampstead Way, 57 flats in The Orchard, and 24 in Temple Fortune Court. Then there were the magnificent shops and flats along the Finchley Road - the work of A.J. Penty, one of Unwin’s team - and - particular success - the clubhouse on Willifield Green. Waterlow Court by Baillie Scott - perhaps the most successful architectural achievement in the entire Suburb - was opened by Princess Louise on 1 July 1909, and George V and Queen Mary, a lifelong supporter of Henrietta, visited The Orchard on 18 March 1911. The foundation stone for St Jude’s was laid on 25 April 1910, the Lady Chapel was in use by 28 October, the whole church consecrated on 7 May 1911, and the tower and spire - a sixtieth birthday present to Henrietta from her friends and well-wishers - was completed in 1913. By this time, St Jude’s first vicar had been chosen and appointed. He was Basil Bouchier and my Mother would often recall the force and wit of his sermons, and how people would fill the church, which is not a small one, and how, when it became too crammed, an overflow congregation would stand outside to hear the sermon relayed by loudspeaker.

So, what had Henrietta achieved during those first twenty-one years of the Suburb’s existence which, we should remember, were preceded by a lifetime of thought and a decade of hard labour in order to realise her dream? She had brought about the creation of a place very much of its time and yet adaptable to the requirements of later generations, a place that is architecturally beautiful, not on a grand scale but of human and truly welcoming proportions, a place of broad streets and flowering trees and green gardens not shut in by walls, and with many, many local amenities. Sir Nicholas Pevsner, that magnificent and industrious critic who chose to live on the border of the Suburb, praised it as ‘The aesthetically most satisfactory and socially most successful of all twentieth century garden suburbs’. Incidentally,  Dame Henrietta realised that a garden suburb was not the same as a garden city, and adapted her plans accordingly. So - was Dame Henrietta - for such she had become by the time she wrote the little book - was she satisfied? The answer has to be a qualified Yes, and an emphatic No. In the very preface to her Story, in the first paragraph, she wrote of what had caused her to write it:

Dame Henrietta realised that a garden suburb was not the same as a garden city, and adapted her plans accordingly. So - was Dame Henrietta - for such she had become by the time she wrote the little book - was she satisfied? The answer has to be a qualified Yes, and an emphatic No. In the very preface to her Story, in the first paragraph, she wrote of what had caused her to write it:

Dame Henrietta wrote her Story in 1928. What of the subsequent years, almost three quarter- centuries of them? Well, the world changed, and the Suburb had to change with it though, thanks to the watchfulness of the Trust, it could have changed a great deal more and very much for the worse. Building for building, it looks pretty much as it did in the early photographs, in spite of the growth of trees and the arrival and proliferation of cars, especially huge 4x4 monsters, totally unsuited to the width, the generous width, of the Suburb roads. People may nibble away at front gardens in order to provide their four-wheeled pets with offroad parking, but no one clads their house with an artificial stone crazy-paving façade. The main change lies in the increase of wealth and in the extraordinary inflation of house prices all over London. Henrietta would be perturbed by that, and she would grieve, grieve deeply, that the Institute has left the Suburb, and she would be working to help it find a permanent home. The bombing of the last war wrecked the Clubhouse; Henrietta would, I think, have been determined to see it rebuilt to the original design.

A century on, the intensity of Henrietta Barnett’s original dream could hardly be expected to endure. House prices have risen, along with inflation, and a new type of resident has come to the area. Yet vigilance, self-restraint and the designation of the Suburb as a Conservation Area have protected its fabric from wanton change. The population is now predominantly middle-class and, on the whole, prosperous, most of the low-rental workmen’s cottages having been sold off by the Trust. People seem to be less sociable, less clubbable, to own more high-tech gadgets, television, hi-fi and so on. Tennis courts are abandoned, allotments overgrown, and the contract gardeners are called in. But at least some part of the original spirit is still there. Neighbours know and greet each other and, when help is needed, it is rare for it not to be forthcoming. The importance of the Hampstead Garden Suburb lies in something more than the plan, or the bricks and mortar; its architecture was intended to express a social ideal as much as an artistic idea; at least a part of Dame Henrietta’s dream has remained secure.

Adapted from a lecture given by Ann Saunders

For in depth research the following bibliography is suggested to assist

Barnett, Henrietta Canon Barnett: His Life, Work and Friends 1918

Barnett, Henrietta Dame DBE The Story of the Growth of the Hampstead Garden Suburb 1907- 1928 Reprinted 2006

Butler, ASG The Architecture of Sir Edwin Lutyens 1950

Creedon, A Only a Woman, Henrietta Barnett: Social Reformer and Founder of Hampstead Garden Suburb Chichester 2006

Gray, A Stuart and Miller, Mervyn Hampstead Garden Suburb Chichester 1992

Hardy, D From Garden Cities to New Towns 1991

Howard, E Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform 2003

Hussey, Christopher The Life of Sir Edward Lutyens 1950

Ikin, CW Hampstead Garden Suburb: Dreams and Realities 1990

Miller, Mervyn Hampstead Garden Suburb: Past and Present 1995

Miller, Mervyn Raymond Unwin: Garden Cities and Town Planning Leicester 1992

Slack, Kathleen M Henrietta’s Dream: A Chronicle of the Hampstead Garden Suburb – Varieties and Virtues 1997

Unwin, Raymond Town Planning in Practice: An Introduction to the Art of Designing Cities and Suburbs 1909

Unwin, Raymond and Scott, MH Baillie Town Planning and Modern Architecture at the Hampstead Garden Suburb 1909

Ward, S ed. The Garden City: Past, Present and Future 1992

Watkins, Micky Henrietta Barnett, Social Worker and Community Planner