Weaponising Womanhood: the representation of women in Hampstead and beyond in the newspapers of WWII

During WW2, newspaper articles, advertising campaigns and radio broadcasts became key factors in shaping and reflecting public attitudes towards gender. With millions of men conscripted into the armed forces, leaving behind an employment vacuum, women were called upon to fill the vacancies.

This signaled (or should have) a seismic shift in society’s attitude towards women and the role/s they were expected to play in a rapidly-changing and uncertain landscape. They became factory and transport workers, engineers, code-breakers, mechanics and much more; all jobs which had previously been reserved for men. But some long-standing prejudices remained entrenched. One Hampstead-born stalwart (of whom more later) was so furious at the War Office’s refusal to allow women to assume armed combatant roles in the Home Guard that she formed her own organization, the Amazon Defence Corps. They didn’t deliver packages (nor, indeed, protect packages from invading Nazis). But they did deliver on their promise to showcase women’s ability to protect the Home Front as well as the home.

This article will explore how the representation of women fluctuated throughout World War II, specifically as depicted in the Hampstead News /Golders Green Gazette.

‘Women and Home’:...

Prior to the war - and in its early stages - the News & Gazette, like many others, featured a regular section dedicated to ‘Women and Home’. These were articles focused on housekeeping, fashion, recipes and moral guidance. They served to promote a narrow view of femininity, reinforcing the belief that a woman’s place is in the home. Often the articles would be written by an anonymous, all-knowing, ‘Housewife’, or even by a male writer, giving them an air of authority.

One article that stood out was published in February 1940, titled ‘How any woman can be attractive’. This headline itself is revealing, as it presents beauty and attractiveness as an obligation expected of all women. The author refers to ‘rules’ that one must follow in order to ‘be lovely’ and the article is structured around imperatives, claiming that girls from the age of 16 ‘must learn’ to use makeup in a way that was deemed as ‘proper’. The article also explains that ‘Beauty culture should start at the age of three’. This frames makeup not as an act of self-expression, as it is more widely seen today, but rather, an essential aspect of a young girl’s edu cation. Strict standards persist into motherhood, with mothers instructed to not wear too much makeup, as that makes one ‘artificial and undignified’. Altogether, this reveals the disturbing extent to which women and girls’ value was heavily placed on their looks and adherence to the rigid standards of the day. This article also quotes Max Factor Jr, president of an American cosmetics company, whose authority as a high-profile entrepreneur reinforces these instructions, highlighting how women’s appearance was policed by both national and international standards.

cation. Strict standards persist into motherhood, with mothers instructed to not wear too much makeup, as that makes one ‘artificial and undignified’. Altogether, this reveals the disturbing extent to which women and girls’ value was heavily placed on their looks and adherence to the rigid standards of the day. This article also quotes Max Factor Jr, president of an American cosmetics company, whose authority as a high-profile entrepreneur reinforces these instructions, highlighting how women’s appearance was policed by both national and international standards.

In the context of 1940, where women were mobilised into the workforce, this article demonstrates the contradictions they faced. Even as they became mechanics, engineers and bus drivers, their ‘worth’ was still largely predicated on their physical appearance.

The ‘Women and Home’ columns disappeared from the paper not long after this article. Upon first glance, this may seem like a sign of progress - that perhaps society was beginning to appreciate women outside the domestic sphere. However, their absence aligns with the intensifying paper shortage during the war. Print newspapers gradually became limited to 25% of their pre-war length and circulation, and readers of the Hampstead News had to place individual orders, rather than easily accessing issues through delivery or their local newsagent.

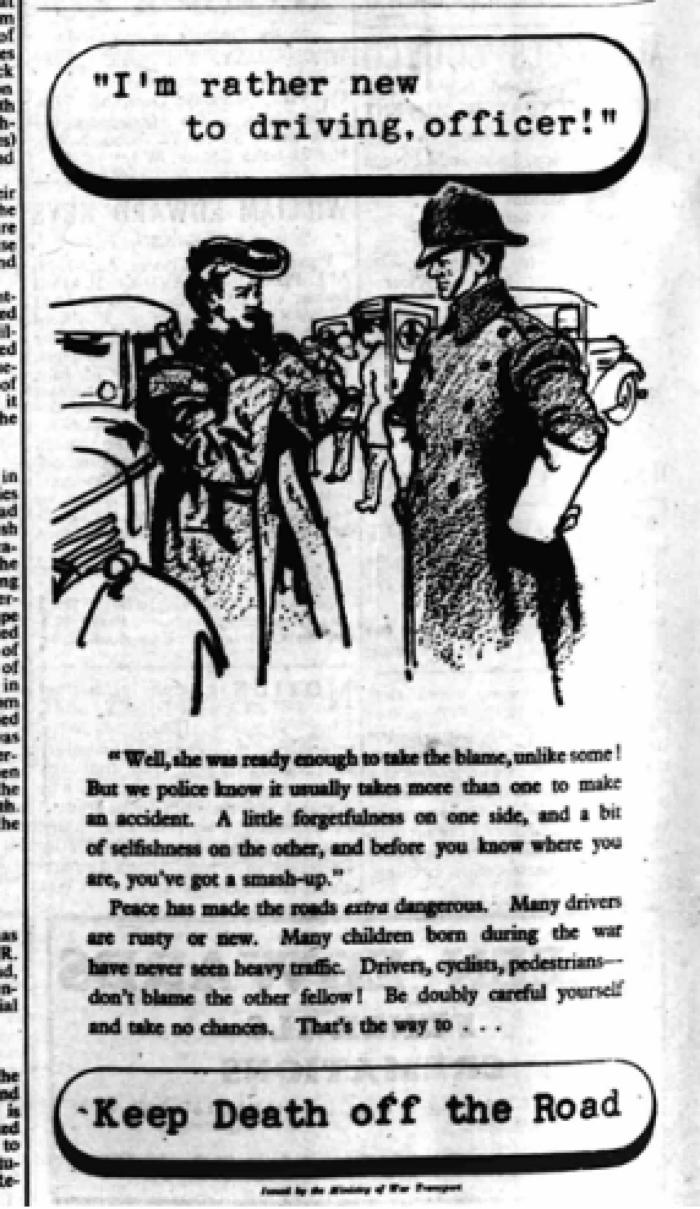

Taking this into account, it becomes more likely that the removal of these domestic columns was not so much a reflection of shifting attitudes, but rather an editorial decision to prioritise space for wartime updates and local news. It is of course important to remember that these articles did indeed appeal to the female readers, whose views reflected the norms of mid-20th-Century Britain. So the removal of these sections didn’t symbolise a move away from these gendered expectations, but instead revealed how such ideas remained implicit, as can be seen in this Ministry of War Transport advert published in late 1945, after the end of the war.

‘Women Drivers’…

The decision to depict a woman as the incapab le driver in this campaign is in contrast to the notion of female empowerment through employment. Traditionally masculine roles such as factory workers, mechanics and drivers had been undertaken by women while their husbands were conscripted. Yet this advert, released so soon after the war’s end presents women as anything but empowered. The image of a woman being reprimanded by a male officer reinforces the age-old stereotype of female incompetence. This emphasis on pre-war gender dynamics suggests a cultural push to downplay the wartime efforts of women and restore traditional gender roles, in order to facilitate society’s return to the status quo.

le driver in this campaign is in contrast to the notion of female empowerment through employment. Traditionally masculine roles such as factory workers, mechanics and drivers had been undertaken by women while their husbands were conscripted. Yet this advert, released so soon after the war’s end presents women as anything but empowered. The image of a woman being reprimanded by a male officer reinforces the age-old stereotype of female incompetence. This emphasis on pre-war gender dynamics suggests a cultural push to downplay the wartime efforts of women and restore traditional gender roles, in order to facilitate society’s return to the status quo.

At the height of war, over 7 million women were employed in England - a significant rise from around 5 million in 1939. This marked a dramatic, but necessary change for a still deeply patriarchal country, with millions of men absent. But even as the female contributions were being lauded, there was unease about how society would be impacted once peace returned. Pressure for women to return to the domestic sphere while men reclaimed their place in the workforce grew. This was reinforced through advertisement campaigns, where women are presented as inexperienced, and in the above mentioned 1945 print advert, a danger to society if left to be independent. Over 16,500 women took up jobs in transport in London, and yet this portrayal of women as incompetent drivers undermines their efforts and achievements of the war.

‘Women at War’…

This transformation of women’s roles was an economic and wartime necessity. But societal expectations were never truly erased. Des pite acknowledging the vital roles that women played in the war, representations in the media clung to outdated stereotypes that reinforced the idea that a woman’s role was to remain within prescribed domestic boundaries. Lord Woolton, the Minister of Food, who established the rationing system, had this message for women:

pite acknowledging the vital roles that women played in the war, representations in the media clung to outdated stereotypes that reinforced the idea that a woman’s role was to remain within prescribed domestic boundaries. Lord Woolton, the Minister of Food, who established the rationing system, had this message for women:

“It is to you, the housewives of Britain, that I want to talk to tonight… We have a job to do together, you and I, an immensely important war job. No uniforms, no parades, no drills, but a job wanting a lot of thinking and a lot of knowledge too. We are the army that guards the Kitchen Front in this war…”

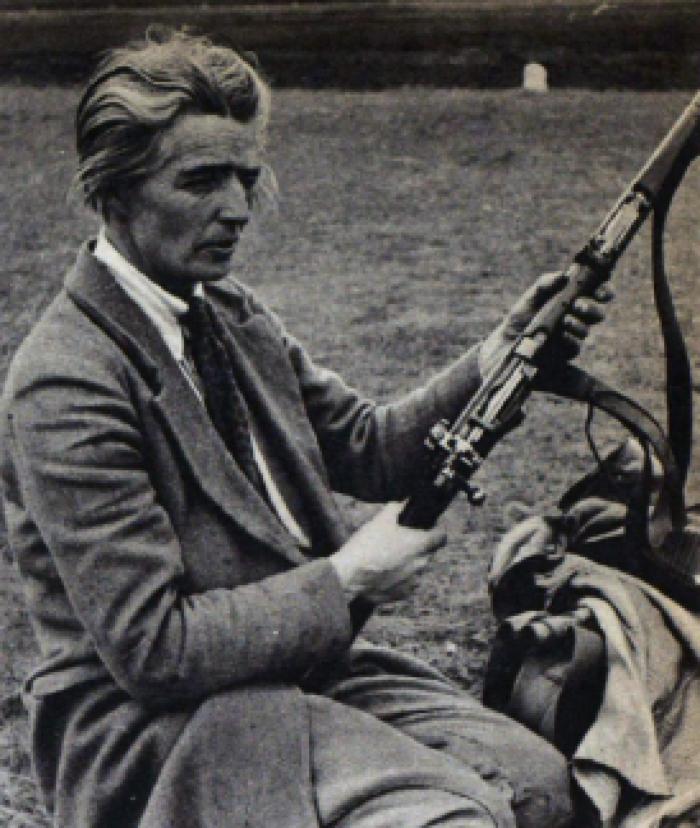

While food management was undoubtedly important, some women felt strongly that they had a contribution to make beyond the kitchen. One such woman was Hampstead-born poultry farmer, ambulance driver and shooting instructor, Marjorie Elaine ‘Venetia’ Foster’, MBE.

At a time when invasion paranoia was rife, and well-to-do women scoured the skies with their opera glasses in search of enemy parachutists, Ms Foster campaigned for women to be allowed to join the LDV or Local Defence Volunteers, later known as the Home Guard.

Snubbed by the War Office, who wouldn’t allow women to join the Home Guard until 1943, and then only in non-combatant roles, Ms Foster’s response was to form her own organization, the Amazon Defence Corps.

Ably instructed by Ms Foster herself - a champion shooter who had received plaudits from King George V for being the first woman to win the ‘Sovereign’s Prize’, the most prestigious trophy in full-bore target rifle shooting (an achievement described by the Daily Telegraph in 1930 as an ‘epoch making event’ ) - the ‘Corps was soon holding weapons training and drill classes across London.

Ably instructed by Ms Foster herself - a champion shooter who had received plaudits from King George V for being the first woman to win the ‘Sovereign’s Prize’, the most prestigious trophy in full-bore target rifle shooting (an achievement described by the Daily Telegraph in 1930 as an ‘epoch making event’ ) - the ‘Corps was soon holding weapons training and drill classes across London.

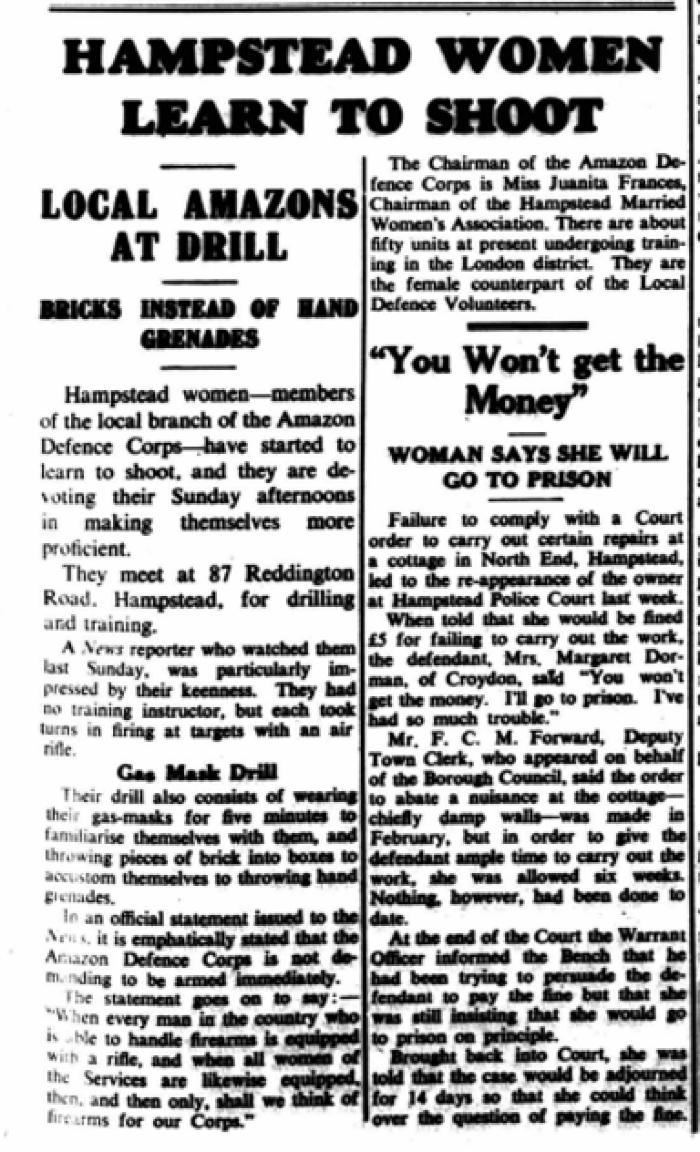

On July 25th 1940, the ‘News and Gazette’ reported that members of the local ADC branch were meeting at 87 Reddington Road, Hampstead, to enhance their combative skills in case they should ever be required to root out fifth columnists or repel an enemy invader.

The chairman of the Amazon Defence Corps was reported to be Hampstead resident, Miss Juanita Frances, who oversaw activities including target shooting, gas mask drills, and throwing bricks into boxes to simulate grenade fire.

Luckily, the Hampstead cadre were never required to test their skills in actual combat with Hitler’s hordes, but the willingness of the Amazon Defence Corps, and other women’s organizations like it, to step up and be counted spoke volumes about how they saw their role in society evolving.

While their wartime experiences didn’t bring about an immediate revolution in women’s place in society, it certainly sowed the seeds for the change that would germinate strongly over the coming years.