Henrietta Barnett School Archives Review

The following review of the Henrietta Barnett school archives has been compiled by Melissa White, a 2018-19 Year 12 student at HBS studying History, English, French and Latin.

"I’m very grateful to have had such an interesting opportunity to learn more about my school while expanding my history skills, and it has been a very fun process! Special thanks to Daniel Harbord and Jean Boal for helping access and collate the materials, as well as to the trustees and archivists and HGS Heritage." July 2019

Henrietta Barnett School and its Outside Relationships

Since its founding by Dame Henrietta Barnett in 1911, The Henrietta Barnett School has always had a special relationship with Hampstead Garden Suburb and its residents. Its role in the Suburb’s social and political development is little-known yet incredibly interesting, with the students themselves shaping the school’s understanding of the outside world over time. Recently I have been privileged enough to look through the school archives which date back to as early as 1926. Over the last few weeks I have put together a project for the Virtual Museum which looks at what the school archives from different time periods of the 20th century, along with my own knowledge of the school as it stands today, can tell an outsider about The Henrietta Barnett School’s outlook on the wider world and how it has changed over time.

The earliest document I found was a school magazine from the summer of 1926, the first of a large collection of school magazines and journals which were published termly for 15 years. A lot of the earliest content relating to this “wider world” theme focused more on the students’ religious beliefs and the decline of the schools’ Christian Association than the student’s opinions on outside political events, but in the magazines published in the years closer to the war there was a significant number of written pieces talking about it. I was surprised both by the amount of content and by some of the views expressed in the magazines, and I also thought it was amazing that the students had been given the opportunities to learn first-hand about the events.

One thing that was consistent in HBS from the 1920s up until the latter half of the 20th century was a practice of taking students on trips abroad to learn about foreign cultures and communities. This was popular among the girls and records of these trips appeared in several different magazines, although sadly they are usually critical and ignorant in tone; the visits are treated almost as opportunities to pass judgement on other cultures. It appears that HBS’ outlook on non-British cultures took longer to develop and improve than their political awareness, maybe due to the lack of diversity in the school until more recent years. The Suburb itself was and still is a white, middle-class area, and as many HBS students used to come from the Suburb and its surrounding areas, this lack of diversity undoubtedly fed into the students’ prejudices which was made very clear in their writing. At the same time, however, the students seem to have had an understanding of the limitations of their environment, as shown through an entry which acknowledges the class-based nature of the Suburb at the time.

The middle of the 20th century saw a somewhat drastic turn in the outside interests of the girls at Henrietta Barnett, with their articles, stories and own poetry published in the school journals beginning to focus on wide-scale social and political issues both in Britain and internationally.

It is evident from the extensive content relating to the Soviet Union and America in the 1961-1967 magazines that the Cold War and the development of Russia was a focal point of interest for the students, extending beyond reading and interpreting news to witnessing first-hand the effects of the Cold War. I was surprised by how invested some of the girls were and the extent to which they went to educate themselves, and I never would have expected to find such valuable material.

It’s not clear whether the students’ mass interest in these political events and ideas was explicitly encouraged by the teachers, but given that so much material appears in the annual school magazines, and also that so much was kept, it is obvious that the school was keen to showcase their knowledge to outsiders.

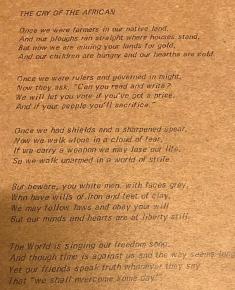

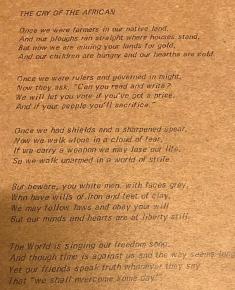

Another popular theme, which I noticed came up a lot in the editions from the mid-20th century, is that of challenging British empiricism and ideas of white supremacy, which nationally at the time were only just beginning to shift; I found multiple poems expressing the unjustness of colonisation, particularly in Africa. There are also two pieces of writing recalling two different students’ first impressions of London, which were fascinating to read and very appraising in tone.

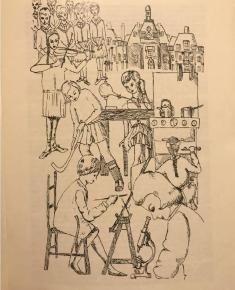

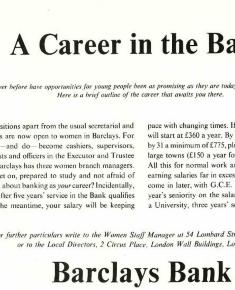

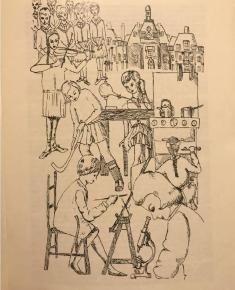

The school’s attitude to the position of women in wider society has been, unsurprisingly, quite positive from early on. Although it is not really touched upon in the earlier archive sets, there was one entry in particular from a post-war magazine that caught my eye: a poem denouncing the idea of women as being “the weaker sex” in what I thought was a really interesting way. Obviously as a girls’ school HBS has always encouragedgirls to break out of and rise above expectations of them as women in the workplace (or just as women), now more so than ever. It was interesting to see that this mentality somehow existed even though lessons in needlework and elocution were still compulsory up until the 1960s. The dual ability for girls to be good at traditional feminine things and also intelligent and self-reliant seems to have been one of HBS’ key messages during the 20th century. It is perfectly represented in the image “Girls’ Activities” which shows drawings of a girl sewing and looking through a microscope. This outlook was evidently ingrained in the students nevertheless, but it suggests that it took a long time for HBS to renounce certain aspects of the original school curriculum for whatever reason.

The school nowadays has a stronger relationship with the wider world than ever before. The political aspect of the school’s extra-curricular life and the students’ ongoing involvement in current affairs are extremely important to the sense of the school as a community and to what the students take away from it. As a student of six years myself, I can say earnestly that a big part of my HBS experience has been the social and cultural awareness I’ve gained in being a student in such a diverse and informed place. Outside events and ideas have definitely infiltrated HBS life in a way that seems to be quite different from how it did 100 years ago, with the students taking a much more active role nowadays in forming their own opinions, arguing their ideas and acting on what they care about. It was so interesting for me as a student and historian to see how HBS’ relationship with the wider world has shifted over time and how that relationship has manifested itself differently through time. I think if anything has remained unchanged in the last 100 years it is that the school and the Suburb have always been a place of great engagement with the wider world and issues of the time, and that HBS’ understanding of and relationship with these things has always been immensely important to everyone connected to the school on an unusually personal level.