War's End

"For four years, wherever we lived or whatever we did, we all suffered. Suffered for different reasons, in different degrees, in personal pain, in sympathetic sorrow, in deep disappointment, in paralyzing pity, in patriotic pride, in unholy hatred — in a hundred ways and each different, we were all united in suffering."

Henrietta Barnett (The Growth of HGS)

The Great War came to an end, at least on the Western Front, on 11 November 1918. The previous four years of hostilities had affected the Suburb in many different ways, but the agony of those who had lost loved ones, and of those who had suffered ghastly injuries, was of a different order of significance to the other miseries inflicted by the war.

Only sketchy figures exist on the number of Suburb residents who served in the armed forces, and the number of those who died on active service, during the Great War. Early in 1916, the Town Crier conducted a door-to-door survey of Suburb dwellings (undertaken by local boy scouts) to gather this sort of information.84 The results, which were published in March of that year, showed over 300 residents on active service or training, and a total of 9 deaths in action. The numbers in the armed forces would have climbed sharply, after March 1916, when conscription was introduced, and the same would have been true of the number of deaths, in view of the deadly battles (such as the Somme) that were still to come. Taking the names of local men on the memorials in just the Free Church and St Jude's suggests that almost 40 residents died in action.85 The actual figure for all residents is likely to have been well in excess of this number.

The war wrought many changes in the communal and social life of the Suburb, but it did little to alter its physical appearance. This is because mounting shortages both of labour and materials hindered housebuilding, and so disrupted and delayed earlier and ambitious plans for its expansion. 'Our beautiful Suburb is hindered in its development', was the mournful observation of one contemporary commentator.86

Between 1907-14, around 1,000 dwellings had been built on the 243 acres of the 'Old' Suburb, an area that formed half of the Golders Green ward of Hendon Urban District.87 Figures quoted by Ikin, indicate that the number of new houses completed in the whole of this ward totalled 432 in 1914, 24 in 1915, 8 in 1916 and zero over the following three years.  The 'Old' Suburb was well developed before the Great War, but plans were afoot, before the outbreak of hostilities, for a major expansion into new lands that had been secured in 1911-12. The HGS Trust had acquired 112 acres, and Copartnership Tenants Ltd - a federal body overseeing the various copartnership companies that were engaged in building houses in the Suburb and elsewhere - had Acquired 300 acres, each being secured on 999 years leases from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. Taken together, these lease holdings - which subsequently were converted into freeholds - describe most of the area known today as the 'New' Suburb.

The 'Old' Suburb was well developed before the Great War, but plans were afoot, before the outbreak of hostilities, for a major expansion into new lands that had been secured in 1911-12. The HGS Trust had acquired 112 acres, and Copartnership Tenants Ltd - a federal body overseeing the various copartnership companies that were engaged in building houses in the Suburb and elsewhere - had Acquired 300 acres, each being secured on 999 years leases from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. Taken together, these lease holdings - which subsequently were converted into freeholds - describe most of the area known today as the 'New' Suburb.

The part of the 'New' Suburb covered by the 112 acres included '... Big and Little Woods, and was developed as Denman Drive, Oakwood Road, Northway, Southway and Litchfield Way'.88 The part covered by the 300 acres comprised all of the present day Suburb to the north of Falloden Way and Lyttelton Road, plus most of the area to the south of these two roads that broadly is bounded by Kingsley Way, Winnington Road and Neville Drive. Some building was underway on these new lands at the outbreak of the First World War, mainly in Oakwood Road and Denman Drive on the 112 acres, and in the 'Holms on the 300 acres, but the vast bulk of the construction on the 'New' Suburb occurred during the nationwide building boom of the inter-war period (in 1919, the HGS Trust transferred its interest in the 112 acres to Copartnership Tenants, so leaving the future development of the 'New' Suburb to be overseen exclusively by the latter).

Notwithstanding the difficulties faced by the construction industry, a small amount of building work continued in the Suburb, at least during the first half of the war. Two noteworthy new buildings were erected in the 'Old' Suburb. In August 1916, the directors of the HGS Trust noted:

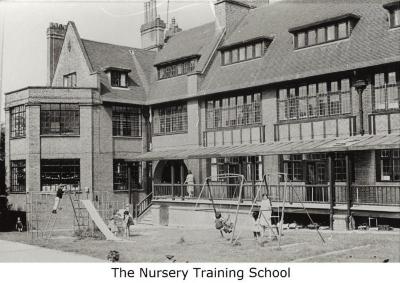

The first... [of these new buildings] ...is the Nursery Training School in Wellgarth Road built by the Women's Industrial Council for training of girls in the nursing of children. The second, a new building to be known as 'The Canon Barnett Homestead' is being completed in Erskine Hill.89

The establishment of the Barnett Homestead was widely applauded in the Suburb, but the same was not true, at least at the outset, of the establishment of the Nursery Training School. This was to be built in one of the 'better' roads of the Suburb, and local residents were not best pleased at the thought of working-class girls (with attendant 'followers'), coming into their neighbourhood to be trained. They wasted little time in informing the Trust of their misgivings. In February 1915, it was noted that the directors had received,'...petitions and letters from residents in Wellgarth Rd objecting to the leasing of Plot 730 for the purposes of a Nursery Training Home'.90 These complaints, however, fell on deaf ears. According to Henrietta Barnett, '...the Directors refused to retract the principles on which the capital of the Estate had been raised, namely to admit all classes of the community to share in the advantages of the Estate'.91

The Nursery Training School opened in 1915, and provided residential accommodation for 60-70 persons, '...half of them tiny children who had lost their mothers, and half young women who...desire specialised training to enable them to tend children...'92 This facility, which became the Nursery Training College after the Second World War, remained in Wellgarth Road until 1979, when its building was sold to the Youth Hostel Association (YHA). The YHA remained there for over twenty years, but in 2007 the building was converted into luxury flats and rebranded as Wellgarth Manor. Applause rather than controversy surrounded the opening of the Barnett Homestead in 1916. Previously, Henrietta Barnett had approached Sir Alfred Yarrow, a shipbuilder and philanthropist, for a loan to build some small flats in the Suburb for the use of war widows with babies or toddlers. Sir Alfred had declined her request, but then made a much better offer. He is reported to have said to her, 'I refused to lend you the money you wanted for the widows' tenements, Mrs Barnett, but I would like to give it to you in memory of your great husband [Canon Samuel Barnett, a friend of Sir Alfred, had died in 1913].' 93 Twelve such flats were built, with the rental income being given to the Institute. Nowadays these flats are bought and sold on the open market, with their original need and purpose having passed long ago.

Applause rather than controversy surrounded the opening of the Barnett Homestead in 1916. Previously, Henrietta Barnett had approached Sir Alfred Yarrow, a shipbuilder and philanthropist, for a loan to build some small flats in the Suburb for the use of war widows with babies or toddlers. Sir Alfred had declined her request, but then made a much better offer. He is reported to have said to her, 'I refused to lend you the money you wanted for the widows' tenements, Mrs Barnett, but I would like to give it to you in memory of your great husband [Canon Samuel Barnett, a friend of Sir Alfred, had died in 1913].' 93 Twelve such flats were built, with the rental income being given to the Institute. Nowadays these flats are bought and sold on the open market, with their original need and purpose having passed long ago.

War or not, the HGS Trust still had to tend to the care and maintenance of the Suburb. In July 1915, the Directors proudly reported, 'The beauty of the Lawns and Public Gardens has not declined, in spite of the rigid economy which war and its demand for labour has made necessary.' 94 The Trust also remained concerned with protecting the architectural heritage of the young Suburb. In this regard, the placement, in August 1916, of a memorial for fallen soldiers on the external east wall of St Jude-on-the-Hill seems to have ruffled a few feathers. Any doubts this may have raised, however, appear to have been put aside because, in January 1917, the directors, '...decided to take no action in regard of the Calvary Memorial' (in 1923, this memorial - which on previous occasions had been visited by King George V and Queen Mary, and also by Princess Patricia of Connaught - was removed from the east wall and brought inside the church, where it is housed today in a shrine room).95

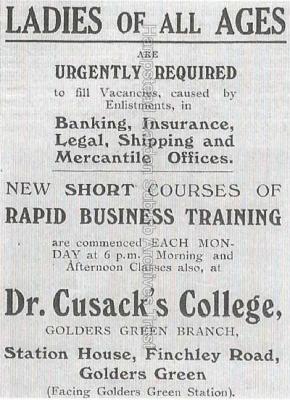

The Trust was not untouched by one of the biggest societal changes wrought by the war, namely the sharp increase in the participation of women in the workforce. In 1914, there were 5.9 million females in paid employment in the United Kingdom, by 1918 the total was 7.3 million.96 Previously, the textile and clothing industries and domestic service had accounted for the lions share of female employment but, during the war, the jobs undertaken by women became more diverse as they stepped into positions in factories, offices and transport that had been vacated by men departing for the front. In the case of the HGS Trust, the roles of company Secretary and of Head Gardener were assumed by women after the male incumbents were conscripted into the army. In May 1917, the position of company Secretary was taken over by Dorothy Thurtle (the daughter of socialist politician George Lansbury), who had spent the previous six months as understudy to a Mr C. E. Ashby pending his ultimately unsuccessful appeal against conscription. Thurtle was left in little doubt that her job was only for the duration of the war. The prefix 'Acting' was firmly attached to her job title.

In the case of the HGS Trust, the roles of company Secretary and of Head Gardener were assumed by women after the male incumbents were conscripted into the army. In May 1917, the position of company Secretary was taken over by Dorothy Thurtle (the daughter of socialist politician George Lansbury), who had spent the previous six months as understudy to a Mr C. E. Ashby pending his ultimately unsuccessful appeal against conscription. Thurtle was left in little doubt that her job was only for the duration of the war. The prefix 'Acting' was firmly attached to her job title.

Dorothy Thurtle clearly was well regarded by the Trust, because she received a 17 per cent pay rise to £175 p.a. in May 1918.97 However, she was forced to step down in January 1919, alter Ashby was demobbed. It can only be guessed how she would have felt if she had known that he returned to his old job on £325 p.a.

If Thurtle, who went on to become a campaigner for contraceptive and abortion rights for women, was a great success, the opposite was true of the female replacement for the Head Gardener of the Trust. In her booklet, Henrietta Barnett noted, '...truth compels me to state that...I would rather work the Estate with men than with members of my own sex'.98 This uncharacteristic remark from such a committed feminist was probably prompted by her unhappy memory of an appointment she had made, in late 1917, of a less than green fingered woman as Head Gardener. The latter, who had been engaged at Henrietta Barnett's own expense, had started work with an equally incompetent assistant who was paid by the Trust. Both women were given the sack in April 1918, when the Trust magnanimously agreed to reimburse Henrietta Barnett half of her expenditure.99

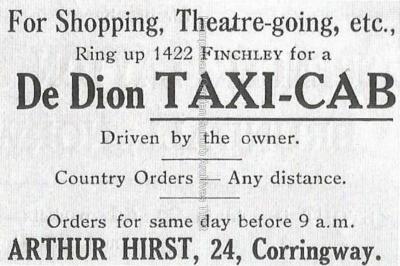

Despite the demands imposed by the war, Suburb residents made a determined effort, at least during its early stages, to realise the Asquith government's objective of 'business as usual'. Ordinary life did carry on. In April 1915, it was announced that, 'With six performances of Ibsen's 'Doll's House' the [Hampstead Garden Suburb] Literary Theatre completes its second season. It can undoubtedly claim to be a remarkable success, as the membership of 500, at the end of the first year, now exceeds 1,500'. 100 Residents were also prepared to travel outside the Suburb to enjoy the theatre, despite the ever present threat of a Zeppelin raid. On the night of 13/14 October 1915, one such raid killed over twenty people in the theatre district around the Aldwych, but the following month the De Dion taxi service, a regular advertiser in The Record, continued to seek the custom of residents requiring transport for 'Shopping, Theatre-going etc.,'.

Residents were also prepared to travel outside the Suburb to enjoy the theatre, despite the ever present threat of a Zeppelin raid. On the night of 13/14 October 1915, one such raid killed over twenty people in the theatre district around the Aldwych, but the following month the De Dion taxi service, a regular advertiser in The Record, continued to seek the custom of residents requiring transport for 'Shopping, Theatre-going etc.,'.

The Institute continued to run a full educational and social programme. In 1916, the directors of HGS Trust were pleased to note that, 'In spite of the conditions of darkness, and exceptional demands on the time of good citizens the Courses, Schools, Societies, Classes and other activities of the Institute have been maintained and the Registers show over 810 fee paying students'. 101 The Schools mentioned in this report were the forerunners of todays Henrietta Barnett School, being a Kindergarten established in 1912, and a High School established in 1914.

The longer the war carried on the harder it became to maintain the pretence of 'business as usual'. Attendances at local social and recreational events, organised by the likes of the Bowls Club, the Ethical Society and the Whist Club, began to decline as more and more residents either joined the armed forces, or volunteered their services in support of the war effort. Volunteering was undertaken on an almost industrial scale in the Suburb. If residents were not sewing comforts for troops, caring for Belgian refugees, or staffing the Garden Suburb Hospital, they were joining the Special Constabulary and filling the ranks of the Volunteer Training Corps. The Great War made great demands on the Suburb, but it also helped to shape its character as a vibrant and caring community.

Life in the Suburb undoubtedly became harsher during the later stages of the war. The introduction of conscription, from March 1916, accelerated the exodus of able bodied men to the battlefields of Europe and the Middle-East, and led to labour shortages at home; whereas the intensified U-boat campaign of 1917-18 reduced the nation's food supply and added a further twist to the upward spiral in food prices. In the Suburb, and elsewhere, great efforts were made to ease these problems, but an understandable fatigue began to set in with each added month of conflict.

Unsurprisingly, the Armistice announced on 11 November 1918 was greeted with a palpable sense of relief. The Suburb had endured but survived four long years of war. The post-bellum mood was captured in the St Jude's Parish Paper of 27 December 1918. In a piece that celebrated not just the end of the war, but also the repayment by St Jude-on-the-Hill of its building debt to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, it was proclaimed, 'Small wonder that Christmas Day this year, what with the sunshine and the cessation of war, was the happiest perhaps that we have ever known, or shall know'. 102 These sentiments would have been widely shared throughout Hampstead Garden Suburb.

This is an extract from the book HAMPSTEAD GARDEN SUBURB DURING THE GREAT WAR by John Atkin. This book was published by the Hampstead Garden Suburb Archives Trust to mark the WW1 Centenary. Copies of the book may be obtained by emailing suburbarchives@gmail.com

84 Town Crier, March 1916, pp. 126-9.

85 Micky Watkins, The Suburb at War, Proms at St Judes Programme, June 2014, p. 14.

86 The Record, December 1916, p. 49.

87 Today the Suburb contains just under 5,000 private dwellings.

88 Mervyn Miller, Hampstead Garden Suburb: Arts and Crafts Utopia? West Sussex: Phillimore & Co Ltd, 2006, p. 30.

89 Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, Report of Directors, 1 August 1916.

90 Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, Minutes of Board Meeting 19 February 1915.

91 Barnett, op. cit., p. 63.

92 Ibid.

93 Barnett, op. cit., p. 70.

94 Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, Report of Directors, 19 July 1915

95 Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, Minutes oj Board Meeting, 2 January 1917.

96 Charman, op. cit., p. 139.

97 Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, Minutes of Board Meeting, 25 June 1918.

98 Barnett, op. cit., p. 68.

99 Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, Minutes of Board Meeting, 23 April 1918

100 Town Crier, April 1915, p. 2

101 Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, Report of Directors, 1 August 1916.

102 St Judes Parish Paper, 27 December 1918.